Patriotism is a veil. It shields you from certain unpleasant facts. Take for instance the civil war in El Salvador from 1979-1991. As Americans, we can take a look at the civil war as a sort of shame. We might have heard senate hearings on C-Span (unlikely) in which our leaders contested the numbers of reported dead. We might have heard something about how the war has lingered on and on. Perhaps we might have even heard somewhere, or seen something about how American interests in the area have prompted our support of one side over the other. But we see it all through the gauze of our cultural mesh. Unless you distinguish the veil from the event, you will never be able to see the situation for yourself.

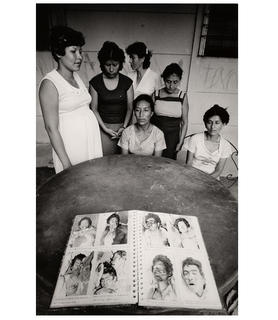

Before you go throwing away a perfectly good piece of linen, though, you might consider keeping it for a handkerchief. What you will see, when you look at the images presented at El Salvador: Work of Thirty Photographers, at the International Center for Photography, may leave you needing a rag for your tears. To abuse Barthes’ terms, the photographs of the exhibition are heavy with

puncta. It could be a small girl in a sundress on a junk-laden street – a setting that could as well be a back alley in a poor area of Charleston, South Carolina. It could also be a soldier’s ornamental belt buckle - something you might find for a few dollars at Urban Outfitters. It could be a boy’s unbuttoned shirt as he stands by a water fountain. There are elements of the image that leave their imprint upon you by triggering your personal somatic-emotional experience. Through this sort of engagement, this photography will place your triggered feelings into El Salvador’s roads, churches and hillsides where the people who suffer everywhere are not just strangers. Without your personal attachment, these people might not transcend the

studium: their significance is tied to your willingness, your desire to absorb their faces into your memory. They can be either victims or individuals, soldiers or boys (often looking to be 12-14 years old). Their faces, postures, the shadows on their teeth and under their eyes may follow you through the other galleries and out into the streets of Manhattan, or they may fold succinctly into your catalogue of atrocities documented and witnessed. From the way I reacted, I think you will find these people to be quite human and irrepressible.

A lasting impression is achieved by a collaboration between the photographer and the subject. There are, to my mind, three interplaying levels of the photograph, roughly related to the foreground, middle-ground and background of a representational visual field. My words for them are the inward, the impassive, and the outward. In one image from the El Salvador exhibition, terrified Salvadorians reach out imploringly to the photographer. In this case, the most potent element in the photograph, the vectors, all push back in the photographer’s direction. The picture being taken is therefore a heavily inward activity. The photograph is well framed so that the imploring faces have plenty of noseroom, but are emphatically presented in screen-right asymmetry. The photographer has stifled his urge to help these people (who are at risk of being trampled) in order to take this picture. The result is that the photographer makes himself passive, makes the picture vulnerable to these aggressive subjects, and the viewer receives the image as though these people are reaching to grab him or her. The viewer is left to internalize the feeling the subject had wanted to impress upon the photographer.

The impassive is an element of a picture in which the photographer engages in a conscious relationship with the subject, who in turn does not reveal all. In this case, the applied aesthetics can only hint at the interpretation sought by the photographer and by extension, the audience. This is the mystery of the picture: the thought on the mind of the child cradling his malnourished belly in Kenneth Silverman’s Las Vueltas. Also impassive is the fierce look in the eyes of the soldier in that same picture, who sets the tone and reflects what the gun barrel at the right edge confirms forcefully – the photographer’s presence in this place, like the civilians’ is perilous, and by association, so is the viewer’s, for that matter. This, to me, is a common element in war photography, in which the situation is unsteady and the picture reveals an uncanny pause in the chaos, as though a short-term truce has been established by the diplomacy of the camera.

Finally, the “outward” elements in the picture are aspects that warrant analysis, but do not or cannot demand it. These are generally framed by the photographer to be absorbed by the audience. A dazzling use of this aspect can be seen in the truck-full of arrested members of popular political organizations in a picture taken by Michel Phillipot. This group has been made to form a pile in a truck-bed like so many bales of hay or animal carcasses. They are closed into the square framing of the truck, and the viewer finds himself closing them into the form made by the soldiers surrounding them. At first, we are not sure of what we are looking at until we grasp that what we see of the detainees are their wrinkled pants and lower legs, face down, showing the scuffed bottoms of their shoes (the confrontational force of the bottom of the feet was something I explored in my own pictures).

The outward elements need the audience to enter into the visual field and interpret, but once interpreted, the elements remain in the mind, held there by the viewer’s implication in analyzing them. The photographer has entered into this situation defiantly and captured it in a way that asks the audience to work for their meaning. The subject has little to do or say on the matter. This is highlighted by the soldiers, who gaze away stoically. In this case, the audience is asked neither to be impressed by the situation (as with the inward elements), nor to defy or confront it (as in the impassive), but to step into it and take part in experiencing it with the photographer.

Please indulge a few words about my own work to prove a point. As I tried to build images out of a few ideas and Zettl’s aspects of Applied Media Aesthetics, I found myself lost analyzing reality. I found myself unwilling at times to even lift the camera to my eye and catch, for instance, an elderly woman bent over her shopping cart, even though I might have been a great distance away. Thinking about subjects as sources of index vectors and as closing into a square, and fussing over the lighting to create flatness or silhouettes was helpful, but I came to understand that photography is as much about the photographer as the subject. When I was ready to take good photographs, I did. All I had to do was stand my ground against my own inclination not to face the situation with my lens. In a sense I found that photographers are very much “agents of death”, as Barthes’ notes. I found myself catching an impression of an instant that has ended. I have marked the end of that instant and that element that will now only be part of reflection. The photographers in El Salvador had a goal: to bring back images to stir foreign audiences into a response to the civil war. They stuck with it and used their skills to fight the war of framing the war. The photographers victimize these people by capturing them in images that reflect some current experience to the viewer, but have long since passed. The moments that the exhibition takes us through are no longer timely in their original context, yet, they last upon our memories like tragedies and memories of the deceased. We cannot help but feel like they will be repeated, that they are elements of a human history.

I think that the best photographs, like Barthes suggests, include a convergence of multiple elements. I like my photograph of my girlfriend passing by an old lady on the street just beneath a sign reading “use two lanes”. It is a bit literal, but it captures a moment with a certain amount of music in it, as though it could continue and lead somewhere and there could be noises and sensations in the air. To me the most lasting and, in the case of El Salvador, devastating pictures are those that contain elements of the inward, impassive and outward in symphony. One such picture is the one entitled La Fosa, by Harry Mattison. A man emerges from the center of the frame, showing his bare back and mane of black hair. He holds a standing baby, dressed in baggy second hand clothing, in his one outstretched hand. They are surrounded by children and adults who are impressed by the spectacle and caught in a moment of suspense as to how long this can last before the baby topples. Yet about half of the crowd is looking not at the spectacle of the standing baby, but at the cameraman behind that spectacle, leaving one to ponder: which is the more essential spectacle? The precarious life of these people, or the photography that enters into their world, is impressed by it, impresses it with an outsiders’ interpretation and yet discovers that they are individuals, to some degree unknowable. Are those people looking at the camera simply wondering what that machine is, or are they confronting us as an audience, asking us what we are going to do about it?

Judge for yourself. And leave the veil behind.